- Home

- Alan Michael Parker

Christmas in July Page 2

Christmas in July Read online

Page 2

Order. It’s like I get to understand everyone, when they come to me, because of course they have to come to me, I’m the Saxon Hills Middle School registrar, and I get to figure out where they’ll go in the system by using different color Post-Its for everyone, in my mind. I get to keep order, to keep everyone where they’re supposed to be. Of course, keeping everyone organized isn’t the same as being organized, and I know the difference.

Positives. The positive paradigm I have about myself: who I am is who I think I am. (That’s from “Teen Empowerment Tips”: be who you are.)

My boys know where I am, always, and they always will. Like I tell them, I’m like a cell phone, only I’m a person, but I’m always on. Lucas is about to start SHMS next year, and he’ll always know that I’m here, in the office.

I saved the second list, the obvious one, the negatives, for tomorrow. It’s the summertime, and there’s no hurry to be negative.

Hello. This is your mother. I wanted to read to you something I found online, it’s a little article. Are you there? Well, your machine can hear me, so here goes.

It’s called “My Good Divorce.” I think that the girl in it is your age, Angela, she sounds like she must be your age. She’s writing on the Internet. One of my ladies gave me the article—she knows I can’t read on the Internet, the screen’s just so small—which was very nice of her. A little bit nosy and pushy, to give me this article for you, Ange, don’t you agree? That’s Mrs. Rakinsumar, she’s from Pakistan, remember?

“My Good Divorce.” Wait, now I think about it, maybe the article was in a magazine, so she’s an expert. I’m looking at the pages now, but I can’t tell if it was on the Internet. How is a person supposed to tell afterward?

“My Good Divorce.” It says, and here, I’ll read it to you: “My Good Divorce. In the fall of 2014, my husband left me for another man. I had long suspected that my husband liked men, from the games he liked to play in the bedroom to the way he looked at my cousin one New Year’s Eve, when we were very drunk together, my gay cousin who was always the most handsome man in our family…”

Angela, are you there? I don’t think I’ll read this to you. I didn’t know it was about gays. I think you have enough on your mind right now.

Sorry to bother you. Byyeee.

Hello. This is your mother. I wanted to tell you that I was looking again at the bill for your father’s procedure, and it must be nothing, it looks routine. He had blood work done, I think, because it’s from a lab, and it’s not even a bill. It says “This Is Not a Bill” in big letters.

Not that he tells me what’s bothering him. Sometimes…I know you don’t like when I say this, Angela, I can tell, but sometimes, you’re just like your father. That’s what I’m calling to tell you. I’m sorry if I’ve hurt your feelings, but the truth between a mother and daughter isn’t about feelings, it’s about what’s good for you. For you and the boys, now that you only have each other, and no one else is there for you, there’s no one coming home. Because I’m your mother.

My, I seem to be very upset today. Must be the heat: they say it’s going to be hot again tomorrow.

If you want to talk later, you can call me up until seven, when your father gets home. Byyeee.

Janet says that a middle school should only have one class, biology, even if they call it all of those other names. Every one of those children becomes hormonal in our building, and then they act so surprised by their changes, and then they get all reckless and stupid, because they don’t know what to do, so then they are incorrigible. That’s a word my dad would use—incorrigible—and it would make a person feel bad, but not forever. Janet says these kids should study biology every day, all day, and then everyone should put on some nice clothes and go to church. Janet approves of church, even if she never goes.

There’s something to say about what Janet says, the way a child can be so calm in the hallway outside the media room, when I’m going to use the Fac/Staff facilities, and I come out five minutes later and that same child’s crying on the floor, and she has torn up all of her class notes—or maybe someone was sending her mean notes, middle school girls, they’re awful—and she’s just a big lump of unhappiness, the poor dear. I ask if she’s all right, and she looks up at me, and her face looks terrible, streaked and puffy, doughy, like a piece of bread, and she looks older by a couple of years. Or she looks like a younger me, but older than herself. That’s when I take it personally: I check to see that no one’s around and I sit down right there in the hallway with her, and I gather up those torn pieces of paper and give her a tissue, and we talk a little while. If it’s busy in the hallway, I take her to my office.

I’m not her mom. I’ve got Lucas and Fremont: I know the difference. I’m not her friend, either. I’m just Ms. Angela Macon, the registrar, but I can see that she’s such a victim of her body and those feelings, and it happens so quickly to girls, those changes, and how do we expect that she’d understand her womanhood quickly, too?

Some of the girls I see, they could be little dolls, they’re so breakable and delicate. They haven’t started their cycles yet—although that’s pretty rare, these days the girls start early—and they seem like they’re wearing Halloween costumes of princesses. Then the next day they’re tall and skinny, and then they’re young women, and then some of them are fully developed women. It’s that fast. There’s a lot of sex at SHMS, much more than there used to be. I didn’t have sex until I was fifteen, but these girls, they’re earlier than me.

The boys are worse off, when they melt down. The boys with their overbites and their noses and feet too big, their voices crack, their eyes look like something’s spinning in there, those panicky boys. Some of them are learning to be mean, to compensate. And it’s not only the big ones. The girls too—cruelty is easy when you’re off balance. That’s “Teen Empowerment Tip” #4: “Being mean hurts yourself the most.”

Here goes my life. I am at the front desk alone, because Janet is down the hall, using the Fac/Staff facilities, and her news from Chicago this morning isn’t good, and she’s taking more time, I encouraged her to collect herself. It’s clear that I’ll be lunching alone. It’s 10:45 in the morning, early for most people to think about lunch, but in July, I think about lunch earlier.

The aunt comes in first. She has on a sleeveless blouse, dark beige or light tan, and a pretty necklace strung with blue and brown and green wooden beads—I wouldn’t wear that, but it works on her—and chocolate slacks and black pumps. Or maybe they’re slingbacks, low heels. She works in an office with a lot of men, I think right away. She’s carrying a medium-sized purse in the bend of her right elbow, the way some women do to make a point, the arm and the hand up, because there’s always a point to be made by certain kinds of women. In her other hand, she’s got a big envelope, which I know must be the papers. She’s maybe my age, mid-thirties, I can’t tell, and she’s working hard to make sure I can’t tell, it probably takes her an hour a day, maybe more. I’d rather sleep than fuss, but what do I know? She’s got someplace else to be. Her hair’s too red. I don’t like her.

Her smile’s better than her body language, though, even if it’s too quick. She looks really tired under all of that, like most of the women I meet who have kids.

The aunt takes three steps into the office, then she notices that no one has followed her: that’s when her smile stops completely. She turns around, goes back to the door, and opens it again, leaning down toward the handle to hold open the door, bobbing her head with frustration. “Come on,” she says. “Now,” she stage-whispers.

The girl’s in a terrible way: she’s tall, hunched over a little to hide how tall, and very skinny. She’s wearing a little skirt—a red plaid, thrift-store schoolgirl skirt—over torn tights, a baggy button-down men’s shirt, and a cap. She’s wearing plaid, up and down, which I’ve seen our girls do before, what a mistake. She looks like a sick lumberjack. She’s got those combat boots, like Doc Martens or some brand I don’t know.

&n

bsp; She doesn’t have any hair under that hat, I think. She might really be sick. She must be hot in all those clothes.

“May I help you?”

“Come on,” the aunt says again. “Yes. Hi. We would like to register Beatrice for school. Beatrice Danzig. I’m Nikki Danzig.”

“Great,” I say. “Nice to meet you. I’m Angela Macon. You’ve come to the right place, and I’m the person for you. Did you just move here? Are you new?” I ask the last question of Beatrice, who stays a foot or so behind her aunt, eyes askance. “It’s a great school,” I say. “Everyone wants to go here.”

“Well, that’s fine,” says the aunt. Her phone gives a quick ting. She reads as she talks. “Beatrice is my niece. She is living with me for now. Hold on—” She shakes her phone in midair, showing me. “Sorry, but I have to answer this.” She waves her purse hand too, but not for any reason. What she hasn’t noticed: there’s a big sign on the main desk, NO CELL PHONES. But it’s okay, it’s the summer.

The aunt steps away from the desk and into the main hallway. The door closes with a last shush.

“Hi, Beatrice,” I say very slowly, the two words separate. Beatrice doesn’t answer. This one’s going to be tough, I think. “I’m Mrs. Macon, in the office. I’m the registrar. Welcome to Saxon Hills—you’ll love it here. Everyone does.”

No reply.

I’ve told her everything already. There’s not a lot to do until the aunt gives me the paperwork. Beatrice and I stand there for a couple of silent moments, me behind the desk and her beneath that awful hat, her illness in rings under her eyes, like ashes.

It’s awful when a child is sick.

“I have two kids,” I say, which is the first thing I say that makes no sense—why do I say this? Then I say, “I’m getting a divorce.”

Hello. This is your mother. Your father says that second marriages are happier than first marriages—I think he means when the first marriage isn’t happy, don’t you? But then, one of my ladies told me that third marriages are the happiest. Like we can just keep trying, and then we get it right.

I don’t think that’s a good idea, being married a lot. I think the boys wouldn’t like it. Of course, I could like anyone you like—maybe not that Tommy, I never liked him—but I could come to like anyone. That’s the kind of person I think of myself as.

Your father says most second marriages happen at City Hall, or they elope. Second marriages happen in secret, I think he means. He wanted me to tell you this about second marriages, I know he did, even if he didn’t say that. I can tell what your father wants.

It’s getting used to someone that I wouldn’t like, I think. Is that what you’re thinking, Angela?

You want to believe you’ve got it together. You want to believe you can go to work in the morning, take the looping path over the footbridge through the yellow woods, through the early light and the thoughts in your head, and there’s Janet, and there’s work to do. Then there’s lunch, then work to do. Then you’re done, you leave, you pick up takeout, and Mr. Ramirez brings his mustache over, and that’s fun, and then he leaves, and you have a drink or two but not three. Then you do it again the next day, and that is the point, doing it all again, knowing it’s happening tomorrow.

Somewhere in there, in the evening, you wait and you wait and then at last your boys call to be tucked in, and you talk with them, and your jealousy makes a vein in your temple go bump—which must be so unattractive—and through all of it, through the beautiful, quiet July evening, you’re fine.

I’m not the girl’s mother. I have kids. And I have Mom, who makes me the one in charge, with all of her questions, who leans too hard on me whenever I need to lean on her. I know she can’t help it, but when I’m in trouble, Mom’s worse. It’s like, psychologically, Mom is giving me signals to be strong by being worse herself. I think she wants me to rescue her so I keep from drowning myself, or something like that.

Janet comes back into the office the same time as the aunt, Mrs. Danzig, and Beatrice hasn’t moved much at all, except to turn her back and look at the Fac/Staff picnic photo from 2013, the one where we’ve all got SHMS T-shirts on over our dresses and jeans and such, and we could be a football team or in the Olympics or something, if we were good at anything together.

Janet gives me the sad eye, so maybe she’s got bad news. She was in the bathroom a long time.

“Well, then,” says Mrs. Danzig. “Beatrice.”

“We’re so happy you’re here to join our Saxon Hills family,” I say. I’m wondering what Beatrice thinks of me, blurting out my business like that. I’m ashamed, but also kind of giddy—a little high on myself, in a way. It feels like a good secret. “I’ve got all the forms here,” I say.

Janet’s been crying, I see now, as she moves around the front desk toward her chair across from mine: she has a tissue clamped tightly in her left hand. She’s squeezing the life out of that tissue. She’s wearing my favorite shoes of hers today, the little orange ones, they’re kind of like sneakers, but they’re shoes.

I’m taller than Janet. I reach and touch her shoulder lightly as she walks by, there, there, and I mean it, and she knows.

“Well, good,” says Mrs. Danzig. “I’ve brought everything. If you don’t mind filling it all out”—she opens her envelope, pulls out a stack of papers, and lays them on the front desk, straightens them for me—”I need to make some calls.”

“Mrs. Danzig,” I say. “We have some forms here for you to fill out. You’ll have to bear with us this morning, we’re just so busy, all the paperwork takes a little doing and it must be done right, and there are only the two of us here, as you can see. So. We’ll need three forms of identification: a driver’s license with a photo ID or a U.S. passport or Green Card…”

She doesn’t like me either, I can tell.

I’m on autopilot, the automatic registrar. I do my job by heart, not thinking too much, pulling the registration forms, asking the questions, showing Mrs. Danzig what she needs to do, getting a clipboard and a pen, listing the documents required, the ones we need to copy—and the whole time, it’s Beatrice who has me spooked, who looks sicker each time I glance at her, who’s the saddest child I’ve ever seen. Something in me begins to fall, I feel it, something’s falling into a hole in me, I’m falling in.

I break protocol. With the aunt assigned all the paperwork, which will take a long while, I turn to look at Janet. She’s holding her head, leaning one hand into one cheek, not good. “Jan,” I say, “I’m going to give Beatrice a tour. Mrs. Danzig, we’ll be back in a few.” I’m not being fair to Janet, I know.

Then Beatrice talks, and it’s the first time, which I didn’t realize until then. She talks, her voice not really her voice, not what I expect from her body, and I know how deep the hole is inside me, how I’ll never find the bottom, it’s that deep. A person should never have such a hole inside.

“My name’s Christmas,” Beatrice Danzig says. “Not Beatrice.”

“We’ve been through this—” Nikki Danzig doesn’t turn from the counter, but she raises her hand and wags the pen I gave her.

“It’s my name,” she interrupts. “I’m not Beatrice anymore. I’m Christmas.”

“In July,” says Janet from behind me. We all turn to look at her, and she gives me a tight smile. I think only I can tell she’s been crying.

“That’s right,” says Christmas. “I’m Christmas in July.”

I grab my purse from the bottom drawer in my desk, snag my zipchain keys from the hook, and try not to look at Janet. I hurt everyone. “Let’s go,” I say to Christmas. “We’ll start at the start.”

We’re in the hallway, and we haven’t said anything. I’ve been leading young Christmas—I like the name, I’ve decided—down through the A Wing into the B Wing and then across the courtyard near the art room, the one where the fire was on the last half day, those bad art kids, probably stoned, and I lead her into the cafeteria, my least favorite area at SHMS. It’s the front, it’s World War

I, the cafeteria. It’s where everyone goes to learn how awful human beings are. Not that I figured this idea out myself: Mr. Binder, the history teacher, said it to me once.

The chairs are up on the tables as though the floor’s been flooded, or will be, the ghosts of all those years of children getting ready to sit on the chairs on the tables. Even when it’s empty, the cafeteria seems so full to me. I don’t turn on the lights. I wonder what the mean ones will do to Christmas here.

“Why’d you tell me that?” Her words hiss a little. She’s not looking at me. “About your divorce. Who are you?”

I think about her questions. “I don’t know,” I say, and realize that I’m answering both questions, why and who. “Why do you want to be called Christmas?”

“Because it pisses her off,” she says quickly.

That makes sense. I want to piss off Aunt Nikki too. “I’m Angela,” I say.

Christmas takes a few steps into the cafeteria, turns or spins, her arms just too long and awkward. “What are we doing here?” She waves at the room.

“So who are you?” I answer, and again, I don’t know what I’m saying. “What am I saying? You’re a girl named Christmas.”

Christmas stops, focuses on me. She tilts her head, squeezes her eyes a little. We’re about the same height, but my god, I must weigh forty pounds more than her, this sick girl, maybe fifty. She’s wearing makeup to cover up the worst part, I think, the darkest circles under her eyes. It’s not working, anyone can see.

“I want…” I begin to say, but then I don’t know what to say. She’s just a teenager: she’s not supposed to die. “Let’s go outside,” I suggest. “Let’s eat lunch on my bench.”

While she goes to the bathroom, I buy snacks from the vending machines: a can of juice, chocolate chip cookies, and chips. I’ll share my lunch with her—that’s my plan—assuming that she eats. She doesn’t look like she eats. I realize I don’t know anything about dying teenagers, or even just dying.

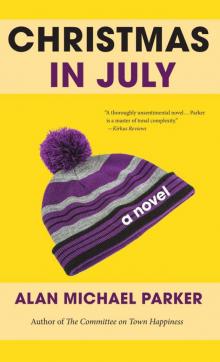

Christmas in July

Christmas in July